Ignacio Ramírez, the man who “came from hell”

News Category: News, Community News, and People of SMA

-

Mexico’s great battles have not only taken place in the military field, but also in the field of ideas, and proof of this is the History of the Extraordinary Constituent Congress of 1856 and 1857 by journalist Francisco Zarco, who was a deputy and was present at its heated debates.

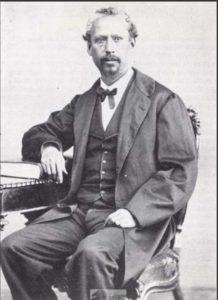

Two decades earlier, another future constituent deputy scandalized a large part of the society of his time, gaining at the same time the admiration of the most brilliant minds of his generation. He was not yet 20 years old and, according to Hilarión Frías y Soto, he presented “a somber aspect, with a long face whose dark color had the greenish reflections of bronze, due to bilious infiltration, a look of fire and prominent cheekbones, which denounced his lineage, an authentic Aztec nobleman, a thick lip that folded into a mocking and sarcastic smile; his eyes sparkled with bright pupils of intelligence”.

The one who had such an imposing figure was born on a day like today, June 22, but in 1818. He saw his first light in San Miguel el Grande -today San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato- and his parents were Sinforosa Calzada and Lino Ramírez, both indigenous. Don Lino, wrote Carlos Monsiváis, “was a liberal and supporter of Valentín Gómez Farías, and his son shared his ideas very early on”. He made them his own to such a degree that the time came when, when he walked down the street, “the vulgar, that is, the majority of the nation, especially the clergy and the wealthy classes, in their fanatical gazmoñería [prudishness], fearfully saw that somber and meditative young man crossing the street.

-That man comes from hell,” said some.Others crossed the street and said from the opposite sidewalk:

-Mason!

-Impious!

-Jacobin!

-Heretic!Expressions to which he used to respond by pointing his finger at us.

-Phoenix! -he would then tell them and make more than one of them run away.

In time, Juan Ignacio Paulino Ramirez Calzada became known as the Mexican Voltaire and the Apostle of the Reform. But also as the Necromancer, a pseudonym that for Carlos Monsiváis “adequately anticipates the dread, the superstitious spirit, the hatred and the “gnashing of teeth” with which Ramírez is contemplated by society” and led some to say that Doña Sinfosora Calzada “was the mother of the Mexican antichrist”.

October 18, 1836, was very important for the construction of his legend. On the rainy afternoon of that day, the young Ignacio Ramírez entered the old Colegio de San Juán de Letrán and went to the space where the Academy of Letrán was in session. Founded by José María Lacunza, his brother Juan, Manuel Tonat Ferrer, and Guillermo Prieto, the Academy became famous for the impulse it gave to literary studies, “seen until then with true disdain”. According to what Prieto wrote in Memorias de mis tiempos: “it was dictated as a fundamental, unwritten law that whoever aspired to become a member should present a composition in prose or verse”, which should be discussed by the members present. Its quality depended on its acceptance.

The Academy was in session on the day in question when, at dusk, the members of the gathering noticed near the door “a motionless and silent lump, which seemed as if it was waiting for a voice to penetrate our enclosure,” Prieto wrote years later in the work referred to.

-What did you command? -asked Andrés Quintana Roo, who participated in the war of independence and was president for the life of the group.

-I wish to read a composition for you to decide if I can belong to this Academy,” answered the apparition.

Quintana Roo invited him to sit next to him and everyone remained silent while the aspirant arranged a pile of papers “of all sizes and colors”. When he was ready, he read in a firm voice the title of his speech:

-There is no God. The beings of nature are self-supporting.-I didn’t hear you, what did you say? -asked Quintana Roo.

Ramirez repeated it and all hell broke loose. According to Prieto’s memoirs:

The unexpected explosion of a bomb, the appearance of a monster, and the resounding collapse of the roof, would have produced no greater commotion.

A rabid clamor arose, which dissolved into altercations and disputes.

Ramirez watched it all with contemptuous immobility.

Mr. Iturralde, the rector of the school, said:

-I cannot allow that to be read here; this is an educational establishment.

And Mr. Tornel, minister:-This is a room in which we are all adults.

-Let it be put to a vote whether to read it or not,” said Munguía.

-I do not preside where there is a gag,” said Quintana, rising from his seat.

Iturralde:-That reading will not be done here.

Tornel:

-It will be done here or at the University.

-Or at my house,” said Don Fernando Agreda, who was attending as an amateur.

Cardoso:-Mr. Doctor, it won’t cost God the presidential chair that reading?

-That will be a blasphemous viborero.

-Sad meeting of literati,” exclaimed Father Guevara, “which becomes a meeting of customs officers, who declare thought contraband; and sad God and sad religion, those who tremble in front of that pile of papers, well or badly written!

-Let Ramirez speak.-Let him speak! Let him speak! let him speak!

And finally, he spoke, generating expressions of horror mixed with those of admiration and approval:

The candidate began to unfold in his dissertation an entirely new and daring theory and in such a way he accomplished his task that the old men of the Academy in spite of the major scandal that the daring orator had given, when he finished speaking they stood up and congratulated him, one of the Lacunza having added:

-Voltaire would not have spoken better on the subject.

Needless to say that he was accepted into the Academy of Letran and that he was one of its most eminent members. 42 years later, on June 15, 1879, after an intense cultural, journalistic, and political life, Ignacio Ramírez died in Mexico City, a faithful witness of his wanderings. Today, which as we mentioned is the day of his birth, these lines seek to remember a fundamental man to understand the Mexican 19th century, a relevant task in our country’s complicated times.

-

Leave a Reply