A new survey shines light on the fight to save Mexico’s native languages

News Category: News and Community News

-

With more than 60 indigenous languages spoken in Mexico, and English and Spanish taking economic precedence over indigenous languages, many of these languages have become endangered. Practices such as Castilianization, which aims to convert speakers of an indigenous language to Spanish speakers, continue to exist in the state of Chiapas and exacerbate this problem.

Preserving indigenous languages can be a challenging task with limited time in school, limited resources, and limited training for language teachers. English-language study materials, on the other hand, are widely available for free online, and qualified teachers are easier to find. Yet, Mexico has also faced difficulties in implementing coherent policies even to promote English programs in schools. For instance, a 2005 program by the Mexican government promoted learning English digitally but was based on the idea that the material included within the program alone would be sufficient for students to reach English proficiency, and that teachers without prior knowledge of English would be able to learn the language alongside their students. During the 2012-2013 academic year, Mexico’s English programs only reached 25% of the students it intended to reach.

Currently, national standards regarding English education mandate that students across all grade levels learn English. Students begin learning English early in their education, but content in English classes is often limited to simple phrases and vocabulary. One reason for this due to a lack of teachers who are communicatively proficient in English. Conversely, another issue is that native English speakers, regardless of their experience or background in teaching English, are often preferred to teachers who have learned English as a second language.

To what extent has the Mexican public even supported language efforts, especially in the context of preserving indigenous culture? We commissioned a national public opinion web survey June 24-26 via Qualtrics, surveying 625 Mexicans via quota sampling. Besides demographic and political attitude questions, we included two questions relating to issues of indigenous groups in Mexico.

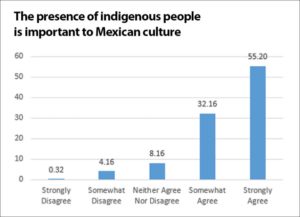

We first asked respondents to evaluate the statement “The presence of indigenous people is important to Mexican culture” on a five-point scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree.

The vast majority of respondents (87%) indicated that they agreed with this statement. Further analysis shows little difference across age, gender, education, or income, although respondents self-reporting as mestizo statistically were more likely than those identifying as blanco to agree.

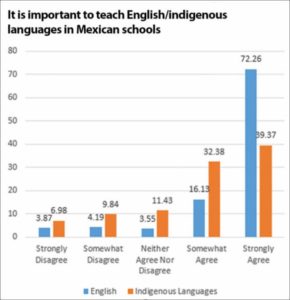

The next question took the issue of indigenous culture from more abstract to more concrete. Respondents received one of two versions of the following prompt to evaluate on a five-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree):

- V1: It is important to teach English in Mexican schools

- V2: It is important to teach indigenous languages in Mexican schools

Though both versions found that a majority of respondents were in support of language education, English surpassed indigenous languages by over 16%, suggestive of the broader incentives behind learning English. Further analysis shows that demographic factors including self-identified ethnicity did not appear to change the preference, although those more likely to agree with the previous indigenous question will be more likely to support both language versions.

English is often perceived as a language of business or a useful means to improve one’s income. Due to this image of practicality, support for English education can sometimes outstrip support for education in a country’s local or indigenous languages, even though English may not have any significant cultural ties in that place.

As indigenous languages gradually disappear from more developed areas of Latin America, the loss of indigenous languages entails a loss of a significant aspect of indigenous cultures. Moreover, lack of education among the general public regarding indigenous languages has placed those who speak these languages at a disadvantage socioeconomically. For instance, studies on Mexican, Guatemalan, Peruvian, and Bolivian indigenous languages demonstrate that the ability to speak an indigenous language is often correlated with limited access to healthcare and education, especially among indigenous women.

The Mexican government has recently begun promoting the preservation of indigenous languages through a branch of the Ministry of Culture called Inali, the National Institute of Indigenous Languages. Inali took advantage of the new virtual formats used during the pandemic to expose hundreds of thousands of people to indigenous languages through comics, books, and other resources throughout 2020. Mexico’s Minister of Culture, Alejandra Frausto Guerrero, said, “Mexico’s greatest strength is found in her diversity of culture,” and emphasized the importance of indigenous languages in that culture. However these efforts, much like with English policies, may poorly transfer to the classroom, limiting proficiency.

For those fighting to preserve Mexico’s indigenous heritage, it is clear that they are still supported — at least in theory — by the majority of Mexicans. However, when it comes to meaningful action, particularly those that could take funds away from other important causes, support may falter.

This piece was co-authored by the following:

Carolyn Brueggemann is an honor undergraduate researcher majoring in international affairs, Chinese, and Spanish at Western Kentucky University.

Isabel Eliassen is a 2021 honors graduate of Western Kentucky University. She triples majored in international affairs, Chinese, and linguistics.

Aurora Speltz is an honor undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Arabic, international affairs, and Spanish.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL).

-

Leave a Reply