New Maximilian biography takes different view on Mexico’s maligned monarch

News Category: News and General Discussion

-

After Mexico won independence from Spanish colonists and declared itself a republic in 1823, foreign rule did make a very brief return to the country nearly 50 years later with the arrival of Emperor Maximilian I.

A member of the Hapsburg dynasty installed in Mexico by Napoleon III’s government and monarchist Mexican politicians, Maximilian spent time during his voyage from Europe to Veracruz in 1864 to accept his crown discussing the history and politics of his new kingdom. Yet he also devoted his energy to writing a 600-plus-page instruction manual on imperial etiquette, including how to pass his hat at ceremonies.

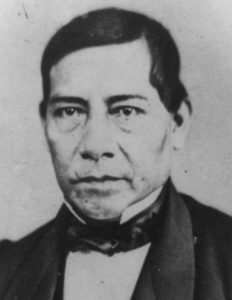

His doomed three-year reign ended in defeat and execution at age 34 by his rival, President Benito Juárez, in 1867, and history has often not recalled his rule or Maximilian positively.

“Maximilian is often portrayed as something of a bumbling idiot, not a very serious guy,” said British historian Edward Shawcross, author of a new biography of Maximilian that presents a somewhat more sympathetic picture — The Last Emperor of Mexico: The Dramatic Story of the Habsburg Archduke Who Created a Kingdom in the New World, published in late 2021 by Basic Books.

“The European context is important,” said Shawcross in a Zoom interview. “He was not necessarily incompetent.”

As proof, the book cites Maximilian’s upbringing as an Austrian archduke in the Habsburg Empire, where he showed promise as governor of the province of Venetia-Lombardy and the commander of the Austrian navy. In Mexico, he gave stirring orations on Independence Day, reached out to indigenous communities and tried the local cuisine.

Yet, he also couldn’t stomach spicy food, and in 1865, when he planned a visit to the Yucatán Peninsula, the deteriorating security situation kept him from going. His wife went instead.

Shawcross’ research on the book dates back to before the COVID-19 pandemic, involving time in Mexico, France and Austria.

How did Maximilian end up ruling Mexico? French forces invaded along with those of the United Kingdom and Spain, as part of a tripartite scheme to pressure Mexico into repaying debts owed. The partnership ended when the U.K. and Spain settled their disputes with Mexico. Meanwhile, Napoleon III and the Mexican conservatives then offered rule of the country to Maximilian.

The brother of the Habsburg emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, Maximilian sought to rule his new empire with both European and Mexican approaches.

“He tried a kind of hybrid,” Shawcross said, “a lot of trappings of European aristocracy. Maximilian loved etiquette, loved hierarchy, [being] deferred to as a Habsburg.” And yet, at his first Independence Day ceremony in 1864, the emperor showed “much more of a Mexican identity, dressing as a liberal revolutionary cowboy.”

Maximilian’s 16th-century ancestor, Charles V, was both the Habsburg emperor and the king of Spain when the Spanish Empire conquered Mexico. “He believed that he was born to rule because he was a Habsburg,” Shawcross said. “[He believed] that he was very talented. There are some indications [that] that is the case.”

“In terms of his character, it’s contradictory; there are different sides to it,” he said. “He’s often dismissed as a dilettante, interested in poetry, botany, an amateur scientist. His horizons were broad. Maximilian also had liberal sympathies by the standards of the 19th century — no autocratic government, a constitutional empire, elements of democracy.”

Maximilian did not journey to Mexico until about three years after the invasion began. The Mexican army had already temporarily halted the French at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862 — Cinco de Mayo.

Despite Maximilian’s doubts about the throne, his wife, Charlotte, a princess of Belgium, encouraged him. “She herself was ambitious,” Shawcross said. “She was decisive and knew what she wanted. … [Maximilian] had ambition but did not know how to channel it.”

Although Maximiliano and Carlota, as they were known in Mexico, established a glamorous court here, Benito Juárez never conceded defeat, and popular support for the imperial rule was anything but overwhelming.

“There are two rival governments,” Shawcross said. “Juárez is wandering the northern deserts, not in great shape, but whole parts of Mexico, north, and south, are not under control. … There was savage guerrilla warfare against Maximilian’s army. [The country] was still torn apart by civil war. It was not what Napoleon III led [Maximilian] to expect.”

Shawcross’ book chronicles Maximilian’s multiple missteps: his liberalism won over some Juaristas but alienated the support of conservatives and the Catholic Church. Adopting the grandsons of Mexico’s first, equally unlucky emperor — Agustin de Iturbide, who ruled from 1822–1823 — mystified Mexicans.

By 1865, when Carlota visited the Yucatán, “The empire was so precarious that he couldn’t leave [with her],” Shawcross said. “He did go on a lot of tours. They were practical. He met the people; it was a chance to get to know the country. Critics said they were real tourists, on holiday away from Mexico City.”

In that year, Maximilian’s empire expanded as much as it ever would, but it was also the year of his hated Black Decree, ordering the execution of any Mexicans who bore arms against the imperial regime and refused to surrender, which generally meant a death sentence for Juaristas.

The Union army also won the U.S. Civil War, and Mexico’s northern neighbor could suddenly pay attention to Mexico again. “They [now] wanted to invade Mexico and drive the French out,” Shawcross said.

Although Americans smuggled weapons to Juárez, in the end, Washington largely used diplomatic pressure. Meanwhile, mounting debts to France violated the terms of the agreement through which Napoleon supported Maximilian.

As the French forces withdrew, Maximilian tried to abdicate on several occasions before being dissuaded — first by Carlota, then by his few remaining supporters.

“She said only a coward would [abdicate],” Shawcross explained. She told him, according to Shawcross, “As long as there’s six feet of the empire, if you’re here, dead or alive, there’s still an empire.”

Carlota left to seek support abroad, first with Napoleon III and then Pope Pius IX, but she suffered a mental breakdown in the Vatican and died in 1927 without ever seeing her husband again.

On Maximilian’s second abdication attempt, he went so far as to pack his luggage. The news got out, but the emperor did not go through with his plan, ultimately resolving to defend his cause with a force of 9,000 — including generals Miguel Miramón, a former Conservative Party president, and Tomás Mejía. They holed up and faced off against the Juarista army of 30,000 in Querétaro city.

“It was one of the worst places in the world for a siege,” Shawcross said. “It was surrounded by hills on all sides. Juárez had the high ground. … Maximilian’s soldiers were starving.

“He showed a sort of great courage under fire. … His point of view was [that] it was an honorable last stand. For two months, March to May, it was a good fight.”

It ended in betrayal and capture. There were rescue attempts from abroad and within Mexico — including from an American supporter, Princess Agnes Salm-Salm. A former actress and circus performer, she implored Juárez to release the emperor to no avail. She and her husband — Prince Felix Salm-Salm, a Prussian veteran who joined the imperialistas — made several unsuccessful efforts to get Maximilian out.

“[Maximilian’s] indecision traps him,” Shawcross said. “It was always the next day, the next day, the next day.”

He was court-martialed, convicted of treason, and executed by firing squad with Miramón and Mejía on June 19, 1867.

In his final months, Maximilian’s indecision may have cost him the most. “There was not much of the empire left to rule,” Shawcross said. “To fight for an emperor who might leave — is this guy worth dying for?”

-

Leave a Reply